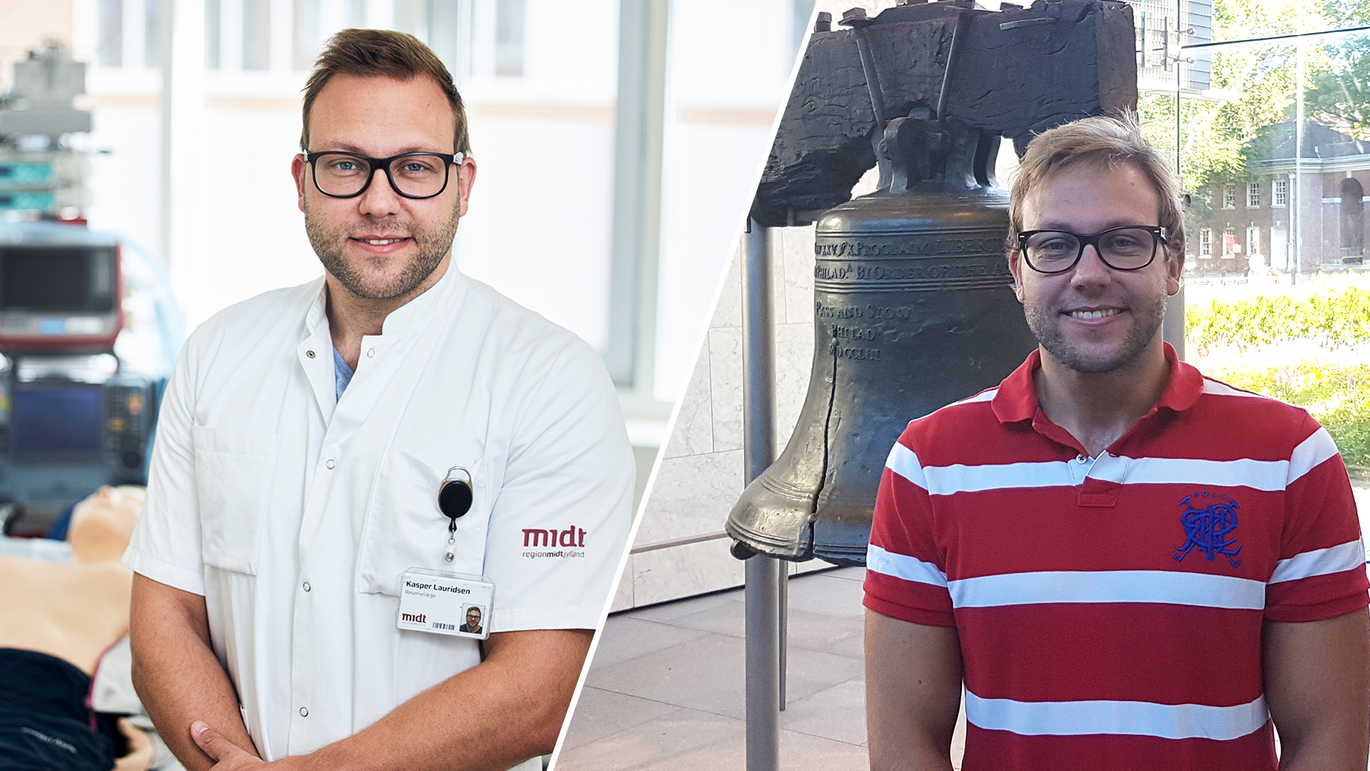

Kasper Glerup Lauridsen: "I sure as heck don’t do research for the money"

The academic career path continues to have its fair share of bumps and dead ends when it comes to equality, diversity, and inclusion. Here, Associate Professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine, Kasper Glerup Lauridsen, shares his experience navigating life within academia.

ABOUT

Name: Kasper Glerup Lauridsen

Title and affiliation: Associate Professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine and Physician at the Department of Surgery and Intensive Care, Randers Regional Hospital

Research areas: Cardiac arrest, treatment of acute patients, and training of healthcare professionals

Age: 36

Residence: Aarhus

Family: Married to Eva, and together they have an 11-month-old son.

"What are you doing here?", a Norwegian senior researcher asked me, looking me up and down, during my first international meeting in South Africa as a PhD student. I was the youngest person there, and apparently, I looked so young that they hadn’t expected to see me in the group. We were working on new international recommendations for cardiac arrest treatment. As a young researcher, it’s easy to doubt whether you have the necessary expertise to speak up and be heard. I’ve allowed myself to be frank and to express my opinions. In my experience, this approach is well-received and garners respect.

I recently took 13 weeks of parental leave. No one batted an eye - neither at the university nor at the hospital. But I also worked during that time. Quite a bit, actually. In the last two to three weeks of my leave, it was practically full-time. I have an upcoming deadline for completing my contributions to the international evidence reviews and new guidelines for resuscitation. If you want to participate internationally, it’s hard to take a complete break from such tasks.

When you have a family, some tasks need to be scaled back. For me, that’s peer review and supervising students who aren’t interested in research. I focus on whether the students are interested in research. If they’re not, we’re not the right match at the moment. On the other hand, I find it particularly rewarding to supervise PhD and research year students. I spend a lot of time on that. Being able to inspire them, help them move forward, and contribute to kick-starting their research careers—that’s the exciting part.

As a doctor, there are plenty of opportunities to pursue a PhD, but getting a research position afterward or finding time to do research is difficult. I think that’s problematic. I’m dual-employed, working 25 % as an associate professor and the rest of the time as a physician in Randers. My associate professorship is 100 % self-funded. My grant funding is about to run out, and I’ll have to go through the whole application process again. It’s going to be tough. I went through the same process three years ago. It should be easier to combine research with medical practice.

Men have better opportunities to apply for grants. There are many of us competing for the same limited funds. It’s extremely competitive. I’m in my mid-thirties and compared to my female colleagues of the same age, I have an advantage because I’ve had more time to publish research articles as I haven’t taken on the majority of parental leave or had to scale back research activity during pregnancy. That’s an imbalance.

I wonder if we’re overburdening female researchers when we strive for gender parity in councils, boards, and committees. It’s a good idea, but if there’s a smaller pool to draw from, is it fair then to ask the 20 % of female professors to take on 50 % of the tasks? I have an international female colleague who said it was a huge problem for her. She was asked to join almost every council and committee because there weren’t enough female members. I think we need to take this seriously. It worries me a bit in regard to our ambitions for equality.

In Denmark, you’re almost out of the game if you haven’t made significant progress in your research career before turning 40. My impression is that you need to publish a lot and early if you want to combine research and medical work. I collaborate with a Swedish research group, and it seems they’re more accepting of research careers that flourish later. It’s okay to prioritize family first and then fully dive into a career in your forties. That’s what a female professor in the group did, and she’s an outstanding researcher, even though she took a few years off for family.

I sure as heck don’t do research for the money. In fact, I’m missing out on money every month. I’d earn more working full-time as a doctor. I also don’t do it for the accolades, although recognition is nice. For me, the biggest motivation behind research awards is the funding they come with for independent research. That’s the kind of funding you’re always short of. I really enjoy doing research, and I hope to keep doing it. I also hope my research is good enough to be noticed and to benefit patients and clinicians worldwide.

ABOUT THE SERIES

The inspiration for this series of articles comes from the Committee for Gender Equity at Health, and is intended to spotlight the career opportunities and challenges junior researchers in particular face in their day-to-day working lives at the faculty.

Each article gives you a glimpse of what working at Health is like for researchers at different career stages and across all of our departments.

In 2023, we focused on work-life balance, and since 2024, we’ve been focusing on the theme of diversity, gender equity and inclusion.

There’s a link to all of the previous articles in the series under this article.