From space research in Antarctica to Aarhus – Nadja Albertsen explores the limits of the human body

Nadja Albertsen has worked and traveled in some of the world’s most inhospitable environments. Today, she applies her experience and knowledge of human physical and mental limits in her research group at Aarhus University Hospital.

How does it feel to work in a world where the sun disappears for four months, temperatures drop to -80 degrees, and the silence becomes overwhelming?

For Nadja Albertsen, an associate professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine, this is not just a thought experiment—it has been her reality on multiple expeditions since she, as a newly graduated doctor, traveled to Greenland to work in a small, isolated settlement.

Since then, she has become the first Danish woman to reach the South Pole on skis and has worked at a research station in Antarctica, where she explored human limits—and her own—in extreme isolation.

Today, her research takes place at Aarhus University Hospital, where she is an associate professor in the Department of Urology. However, her fascination with the human ability to adapt to extreme conditions remains a key focus of her work. She is particularly interested in how we perform under extreme pressure.

“I like to push myself beyond my limits, and I am drawn to places where humans are not really meant to be. There is something fascinating about being in an environment where nature sets the agenda, and you have to adapt on its terms,” says Nadja Albertsen.

For her, expeditions have not only been about overcoming physical challenges but also about gaining a deeper understanding of herself.

“When you are isolated for months, you realize what you truly miss—and, just as importantly, what you can easily do without.”

Got a taste for adventure in Greenland

When Nadja Albertsen first traveled to Greenland as a newly graduated doctor, it was only meant to be a short-term stay.

But the nature of the work and the raw, untamed landscape left a much bigger impression on her than she had anticipated.

The plan was to stay for just two months, but she ended up staying for three years. Three years filled with unexpected experiences and challenges that required her to think creatively to solve problems far beyond what she had learned in medical school.

One day, for example, she was asked to examine a piece of a recently hunted polar bear, which someone from the village had handed to her in a potato chip bag. Eating polar bear meat can be dangerous if it contains parasites.

“I hadn’t exactly expected to be checking for trichinella in polar bear meat under a microscope, but it was actually pretty fun—and with a little help from Google, I managed to do it,” says Nadja Albertsen.

Her time in Greenland gave her both hands-on experience working under harsh conditions and a deeper understanding of how much the human body and mind can endure.

“You suddenly realize just how much your body and mind can handle when there’s no turning back—when you simply have to keep going, no matter how exhausted you are or how extreme the conditions become,” she says.

“And I discovered that I thrived in these extreme environments—that I actually enjoyed being in a place where you have to be entirely self-reliant, where you develop a completely different relationship with nature and your own limitations.”

Space research in Antarctica

After three years in Greenland, Nadja Albertsen returned to Denmark in 2016 and began her specialist training in internal medicine in Aalborg.

However, her desire to work in extreme environments did not disappear.

“Taking a step into the unknown has always attracted me. I think it’s healthy to push yourself and experience that doubt you feel when you’re standing in an airport with a knot in your stomach, wondering: ‘What am I getting myself into?’ When I saw that the European Space Agency (ESA) was looking for a doctor for the Concordia research station, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to combine adventure with science,” says Nadja Albertsen.

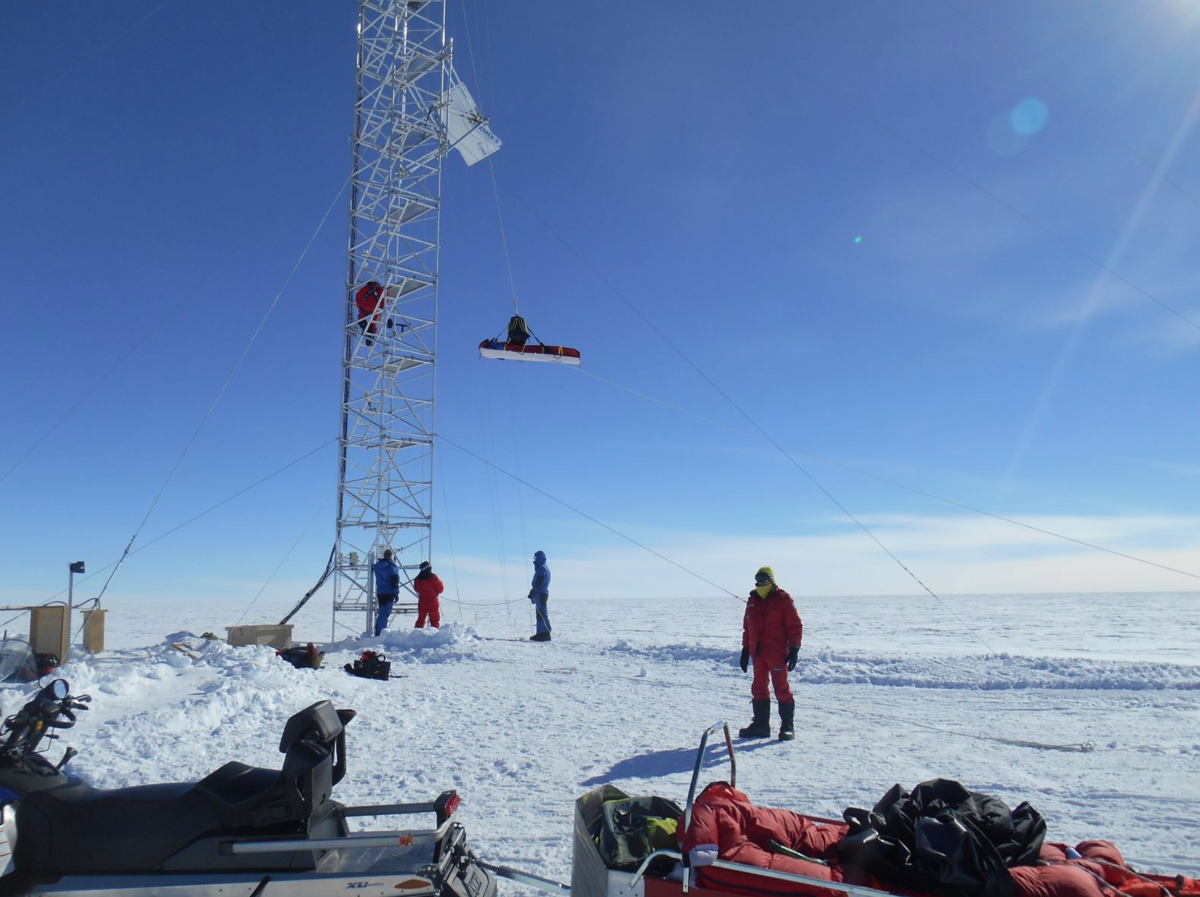

At Concordia Station, one of the most isolated places on Earth, researchers live and work under extreme conditions. The purpose is to simulate the conditions of Mars and study how the human body and mind respond.

ESA was seeking a doctor responsible for conducting research on how isolation, lack of sunlight, and extreme cold affect the human body.

A great mental challenge

ESA had strict requirements on the Concordia crew, who had to endure long periods of complete isolation, constant light conditions—either total darkness or midnight sun—and limited contact with the outside world.

“It is a great mental challenge to be isolated for such a long time. But it was also a unique opportunity to experience how humans function under extreme conditions and to contribute to research that could help us better understand human adaptation, including in space exploration,” says Nadja Albertsen.

Nadja Albertsen applied for the position and was selected from among numerous candidates across Europe. From November 2018, she could call Concordia home for the next 13 months.

Four months without sun

It is not only the isolation that makes Concordia unique. The station is located at an altitude of 3,200 meters, where oxygen levels are low, and temperatures fluctuate, reaching as low as -80 degrees Celsius. All of this requires constant adaptation from the human body.

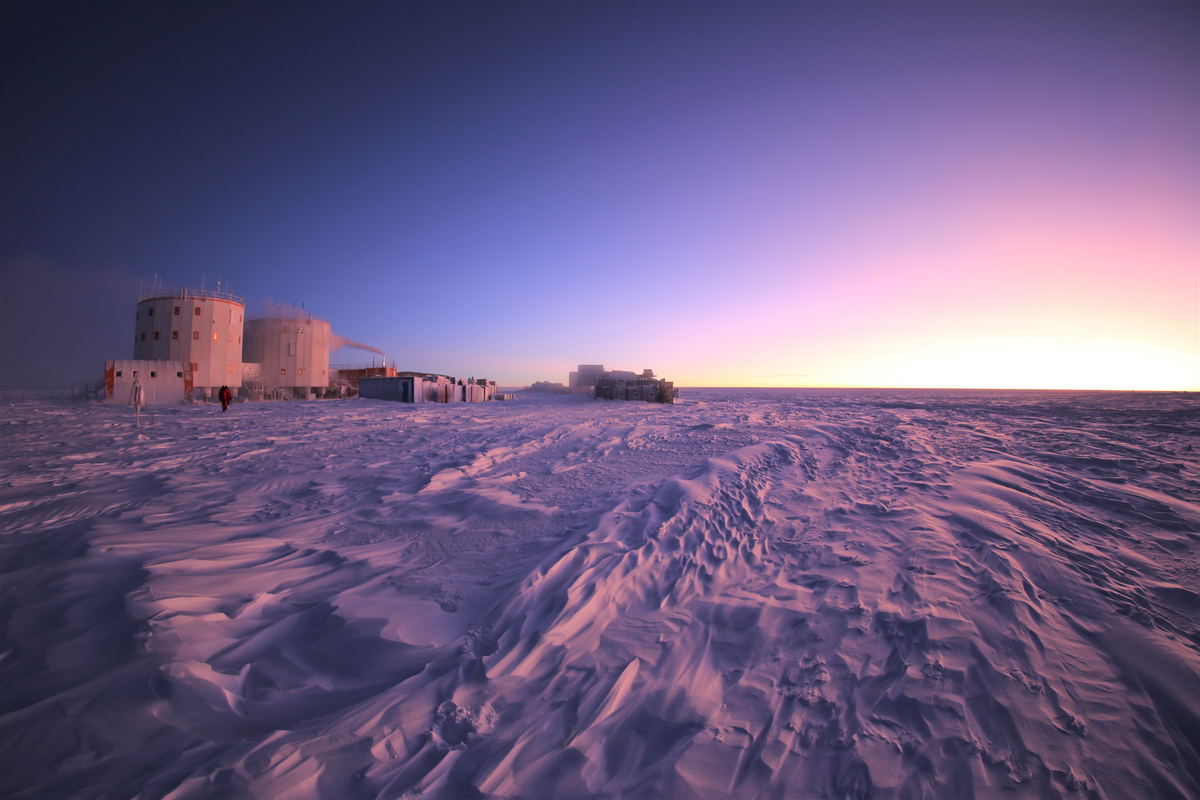

One of the most memorable moments was when the sun finally returned after four months of darkness.

“When the sun finally rose again in August, it marked a turning point. The temperature would soon start rising, the ice would disappear from the windows, and we could once again see outside the station. At the same time, the dark, starry nights transformed into a sky bathed in stunning colors – especially the purple hues that dominated for a while, which I remember as particularly magical.”

“It was beautiful, but also bittersweet because it signaled the end of our stay and a farewell to the small family we had become,” says Nadja Albertsen about the 13 people who made up the winter crew at Concordia.

Home again

After her time at Concordia, Nadja Albertsen has used her research and experiences to shape her career.

In January 2023, she became the first Danish woman to ski to the South Pole. This was part of the Inspire 22 research expedition, during which she spent 48 days in Antarctica’s so-called white desert collecting data on how extreme conditions affect the human body.

In 2024, she completed her Ph.D., focusing on the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Greenland.

She has since brought that expertise to Aarhus, where she now works to understand how humans perform under pressure—not only in extreme environments but also in healthcare.

Today, she is an assistant professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine and is based at the Department of Urology at Aarhus University Hospital.

She is involved in a project that examines the training of young surgeons through a holistic approach inspired by military methods.

Together with Professor Jørgen Bjerggaard, she has also helped secure funding for a project investigating the psychological effects of a lack of intimacy in space.

After spending years in some of the world’s most unforgiving environments, the contrast to her current work is striking. Now, at AUH, she can carry out her research in a comfortable indoor setting—without a heavy down jacket, mittens, or fur-lined hat.

While she still has a passion for adventure, her priorities have shifted.

“I have enjoyed the freedom of my previous positions, and as a young researcher, you have to accept short-term contracts. But I can also feel—perhaps it’s age catching up with me—that I would really like a permanent position. Not constantly being on the move toward something new or having to figure out what the next step is,” says Nadja Albertsen.